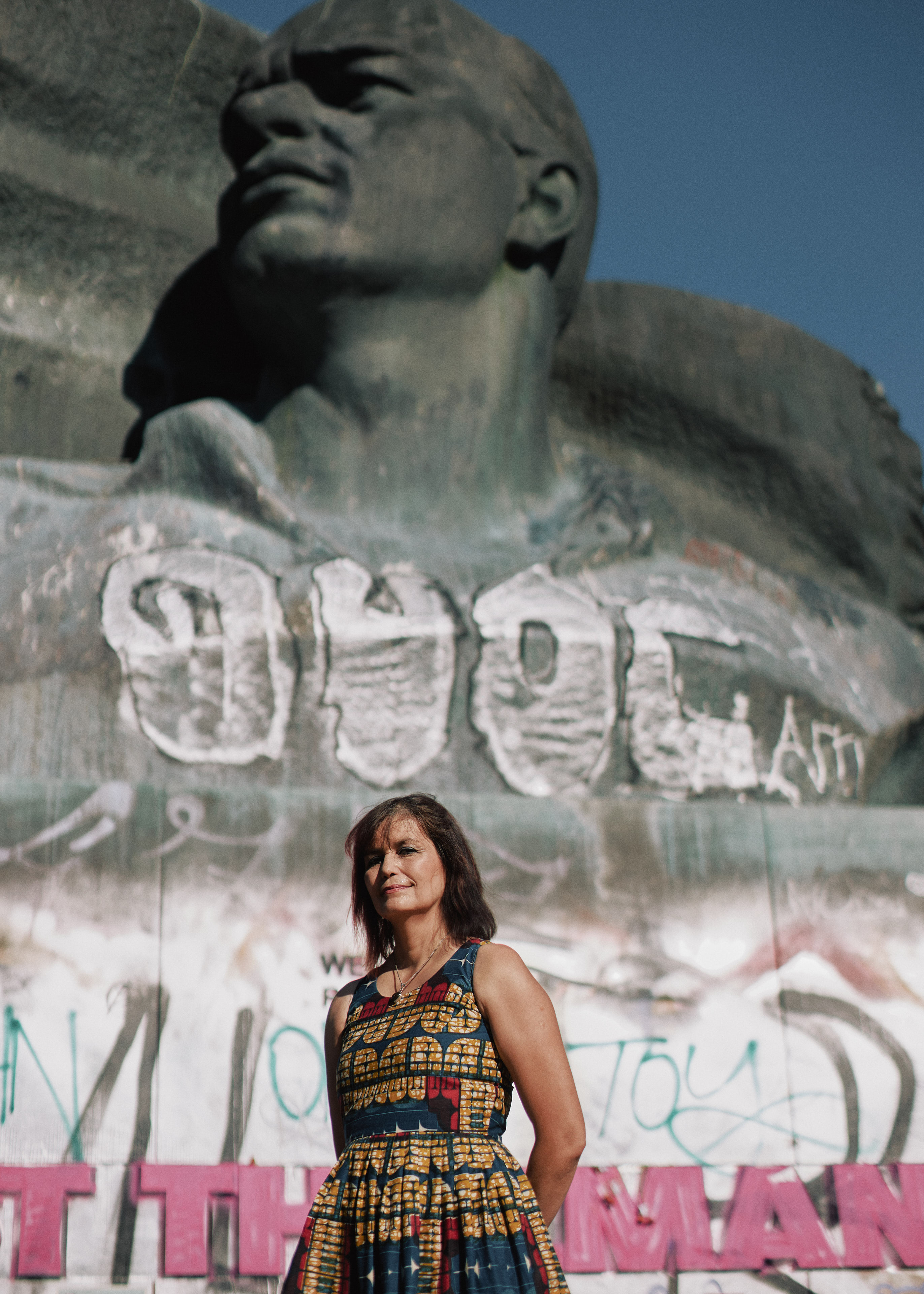

Monica, Berlin

“My mother raised me alone. That gave me a good feeling of what it actually means to have a child.”

I never saw myself as a mum, I never had dreams of having children. It’s never been a struggle, a question, even a decision, for me.

I remember when I was six or seven, people asking my friends and me how many children we wanted. Everyone else had an answer, like, “Oh, I want two girls”, or, “I want a boy and a girl” – because, in Spain, you have the parejita, the little couple of a girl and a boy, which is the perfect thing to have. But I never had an answer for that, because my default was, “I don’t want children”.

I was born in El Salvador, and we moved to Barcelona when I was four and a half. My upbringing was very Catholic, which says that you definitely have children at all costs. You should bring that light into this world, even if you got pregnant under the most dramatic circumstances. My mum was one of nine siblings, and all my cousins, all of them, have one or two or three children since their 20s.

My mum is a single mother. She arrived at a point where she wanted a child and just went for it. She didn’t care too much whether it was in a marriage or not, and she had a good job and could afford me. She decided she didn’t want to raise me in a civil war, so she took the opportunity to go to Spain.

My mother had always lived with the support of her family, and suddenly she was alone in another universe. It was tough back then. Now there are so many Latinos in Spain, and people from all over Africa, who came in the 2000s. But when we arrived, nobody really understood immigration – there were Spanish people all over the world, but the country wasn’t used to receiving people. There was no Skype, or WhatsApp – my mum would send letters to her family.

So she raised me alone. And that gave me a good feeling of what it actually means to have a child, the struggle of juggling a career and always trying to find someone to take care of me. I grew up very independent and aware, a person of my own – even as a child, people would call me an old soul. I always say I’ve been raised more German than Mediterranean, and that’s why I fit in here. I’m used to going into things on my own. And I’m very grateful for that, I think it’s an advantage. But it is a consequence of my mother having to raise me alone.

“Being childfree is a gift, because I can focus on what I want to do in my career, and my own contributions.”

Being childfree is a gift, because I can focus on what I want to do in my career, and my own contributions. Selfishly and naively, I thought all the drama about being a mother and being less hireable would never affect me. Until I was 35, when I decided freelancing wasn’t for me, and wanted to jump back into being an employee at a company.

I don’t want to sound arrogant, but in the past I never struggled to find a job. What’s been hard is not taking the first thing that comes to me. I’d be on the market one month max – search, apply, pass the interviews and have a new job. But last year, suddenly, it was a struggle. I was doing 10-15 interviews a month, and wasn’t getting past the second screenings. After three months of that, I was getting really concerned, thinking, “What’s wrong? Did I get outdated? Am I not valuable anymore?”

I spoke about this with my best friend, who’s had more experience in the job market, and she said, “You know what Monica? I think you should start saying in interviews what you don’t want children”. And I thought, no, Germany isn’t like Spain, surely this isn’t a consideration. But the idea stuck in my mind. This was the end of November, and I really wanted to start a new job in January, so I had six interviews lined up in December.

I didn’t have much hope. But I did the interviews, and very subtly, I’d bring up the concept. So when they’d ask, “What do you do in your free time?”, I’d mention the meetups that I organise, Dog Lovers in Berlin and Childfree in Berlin. “Oh what’s ‘childfree’?”, they’d ask. “Well, you know, I don’t want children, so I realised that when I’m 40 or 50, I’ll probably need a network of friends who don’t have kids either, so I’m not alone.”

“It’s a societal problem. It doesn’t matter if you want children or not, these biases will be applied to you.”

The results were staggering. Of the six interviews, I passed five second rounds, four third rounds and got two job offers. I don’t think it’s a conscious thing that the companies were doing. But they had six, seven candidates, and they had to cut somewhere. And they’re looking at me, my age, and wondering why I’d want to go from freelancing to full employment. Of course, no one can ask me directly, so they’ll just assume it’s time for me to have a child in peace, that I want the job for the parental leave and would immediately get pregnant.

I don’t see any malice in this. I’ve worked in hiring, and I know that the unconscious bias is there in all of us – men, women, everyone. And anyone who wants to deny this is just being politically correct or trying to protect themselves from a lawsuit. Companies will always look after themselves and what’s best for them.

It’s a societal problem. I’m absolutely not saying that someone who’s about to have a child is not a good person to bring on board – I think mums are the most organised, productive, effective, and smart people out there, because they’ve had to strategise their lives. What I’m saying is that this affects us all. It doesn’t matter if you want children or not, these biases will be applied to you.

I was talking with a friend who works at an engineering company, and he’s like, “Monica, this happens to men too. Our hiring pool is mostly men, and this is still a consideration, because if they are in their 30s and don’t have children yet, we know what’s coming.” That’s horrible. But it gives me hope. Because it means that as long as countries give the same rights for men and women to take parental leave, then it levels the field.

“I’m meeting more and more young women who tell me, ‘I don’t want to have children’, and that makes me really happy. That’s a privilege we have, and it’s a privilege we have to defend.”

When it comes to healthcare, I’ve been very judged and not taken seriously about the fact that I don’t want children. I think my life would be so much better if I could get sterilised, so I’ve asked about it and been dismissed. I was met with a, “No, this is never going to happen. Not with me as your doctor. Finding a doctor who will do this for you might take years of research and paperwork. And by that time, you’re going to be 45 or something, almost in your menopause. Good luck with that.”

I’ve had nightmares about being pregnant, unable to abort, and having somebody growing inside of me that I don’t want. Yet, somehow, I’ve accepted this dismissal as a first-world problem – I know there are worse cases, and that’s where I put my energy. I don’t think it would be easier in Spain, but I used to think that Germany was a more progressive country – at least, that’s the perception. Germany is as sexist as Spain, but in other, more subtle ways – it’s not as in-your-face.

When I was in Thailand, I met someone from Finland who’d travelled there for a procedure, like lots of Europeans do. The country has great medical staff and is famous for its amazing healthcare system. This woman had endometriosis for many years, didn’t want children, and was there for a hysterectomy. The doctor had said to her, “The most important thing for us is that you’re happy, that you have your health and your peace of mind. Think about it for three months, and, if you think you’re truly going to be happier living pain-free without your uterus, then I’ll do the procedure.”

This woman was so happy. She said, “I really appreciated that, for them, it was not about anyone else but me – what would make me happy and improve my quality of life”. That should be at the core of all healthcare. But, in Western countries, especially conservative Germany, there’s this idea that we, as women, can’t make these decisions for ourselves. This is crazy.

I am thankful that I live in the 21st Century, so if I did get pregnant I wouldn’t have to have the child. If I was born 50, 100 years earlier, I might have ended up either raising an unwanted child, or giving it up for adoption. I’m meeting more and more young women who tell me, “I don’t want to have children”, and that makes me really happy. Because they are realising that they have options. That’s a privilege we have, and it’s a privilege we have to defend.

Follow Monica on Instagram

Photos by Zoë Noble

Words edited by James Glazebrook